A good seven/eight years after I started reading at her

website, I finally got a copy of Mrs. Clark's "The Dressmaker's Guide". I hadn't done so at first, as I was 1) at college, with little spending money, and thus 2) on hiatus from the hobby. By time I got back into the swing of things, I felt confident on the basics, and didn't think I'd have much to learn from this particular source.

This turned out to be--very much--not true.

The book is divided into twelve chapters, detailing how to drape or draft and then make up each of the layers* which goes into women's wardrobes c. 1840-65. The first three chapters cover preparation for sewing and context for one's living history: a year-by-year timeline of events, approaches to progressive reenactment and documentation of research, a timeline of dress styles, and a 50-page tutorial of stitches and fabric terms. Chapters 4-11 go through each garment or element, discussing how to fit it, what materials to use, and how to make it. Chapter 12 is a quick-reference appendix, with three "croquis" in different body types (instructions are given in chapter 2 for using these paper dolls to plan your outfits and play with styles).

For a preview of style and content, the free women's patterns found at the

Compendium are mostly taken from the book (except for the sunbonnet, shawl, and apron). The chemise chapter, for instance, includes the personally-drafted banded chemise found at the Compendium, as well as instructions for a gored chemise, and a discussions of the different fabric choices. Similarly, the basic drawers and petticoat are given free on-line, but the book offers additional design choices, including decorative tucks and whitework insertions, and instructions for corded and quilted/wadded petticoats. If you can follow the directions given on-line, you'll have no trouble with the book's instructions. Additional book content includes a whole chapter on draping a personal corset pattern, cage crinoline instructions, a self-drafted sleeve pattern with 8 different variations, and a chapter on personal accessories.

What I found most valuable were the bodice and sleeve drafting instructions. Several variants were included for each, with the time period when each is popular, and instructions for personalized fitting. To get an idea of the breadth of the bodice chapter, take the

"Having a Fit" article, then add sketches of each step for the draping, advice for fitting commercial patterns, and instructions for creating 6 different bodice variations from the basic pattern (high or low, gathered or darted, V-necks or rounded, and some beautiful pleated/shirred "fan fronts"). The sleeve portion follows, and I'm excited to experiment with some of the variations shown.

I expect this book will prove valuable to sewing enthusiasts of all skill levels. Despite extensive reading on the subject, I was surprised by new elements like the diagonal tucks. At the same time, all the basics are present. A person with no experience in mid-19th century women's clothing could go through every step from selecting an impression to finishing a completed ensemble with the instructions given here. It may take a while, by the information is all given in a clear manner which should be accessible for beginners. Additional help is available through the author's website, or at the attached

forum.

Looking for downsides, the main things which come to mind are the overall size: there are 100 pages of information before any garment instructions show up. This is possibly overwhelming, but also provides interesting background information and useful techniques. The instructions can at times 'run-on' in my opinion (separate tables for calculating yardage for each type of petticoat, for instance, instead of just adding or subtracting from the basic plan), but this may be useful to those not mathematically-inclined or who need to take some things in 'baby-steps'. Erring on the side of more information and simpler explanations isn't a bad thing. For those that need visual instructions, there are nice sketches included with most of the techniques, but no photographic images of garments or steps. I liked the drawings as given; your mileage may vary. The table of contents gives page numbers for the chapters, but the one thing I would change about this book is adding a topical index,*** so you can look up "coat sleeve" or "petticoat: whitework" and go directly to the page.

Score: 5 Stars

Difficulty: Absolute beginner & up. Basic sewing skills are useful, but not strictly necessary.

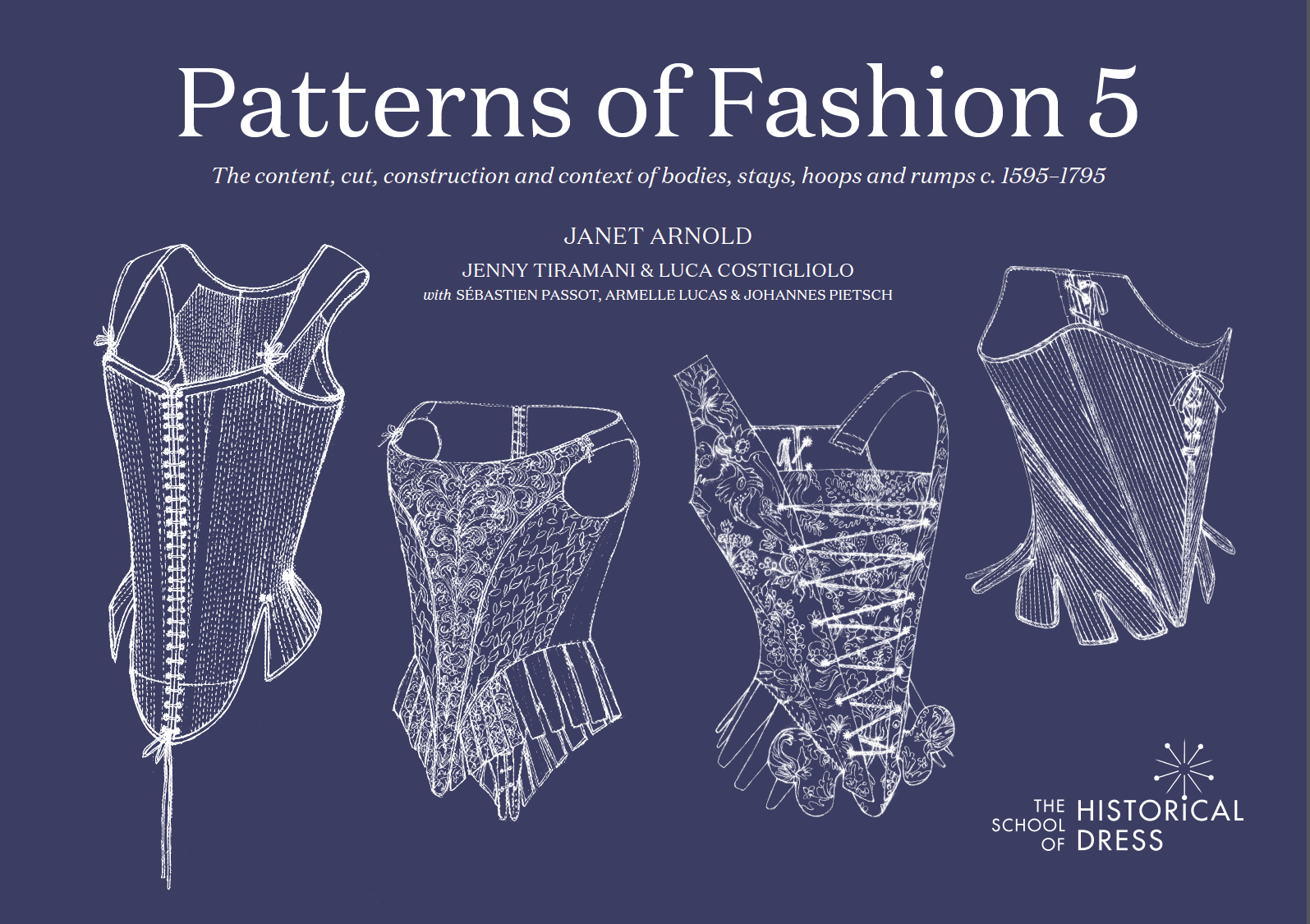

Accuracy: No original garments are presented, but the variations and techniques are all very accurate as far as I can tell. Read Janet Arnold if you want details of original garments, this is more a summary of the the period and its aesthetics.

Strongest Impressions: This is a book to reference. It's not meant to be the end of your research, but the beginning. Find an original for inspiration, then use the sketches and instructions in here to reproduce the elements you like. The introductions and instructions in chapters 1-3 are a good basis for making one's first forays into historic clothing--and will put you miles ahead of the non-fitted, ready-mades found at most reenactments. Should I even become an eccentric millionaire (half-way there!), I would be giving these out like Bibles.

*On further reflection, stockings & garters, shoes, gloves, and millinery are not included as topics. All trunk garments from the chemise outward are covered, however.**

**Ok, not aprons. But you should be able to figure one out from the all the techniques given.

***Edited to add (11/28/14) that a printable index is now available

here. Rumor has it that future editions will include an index.