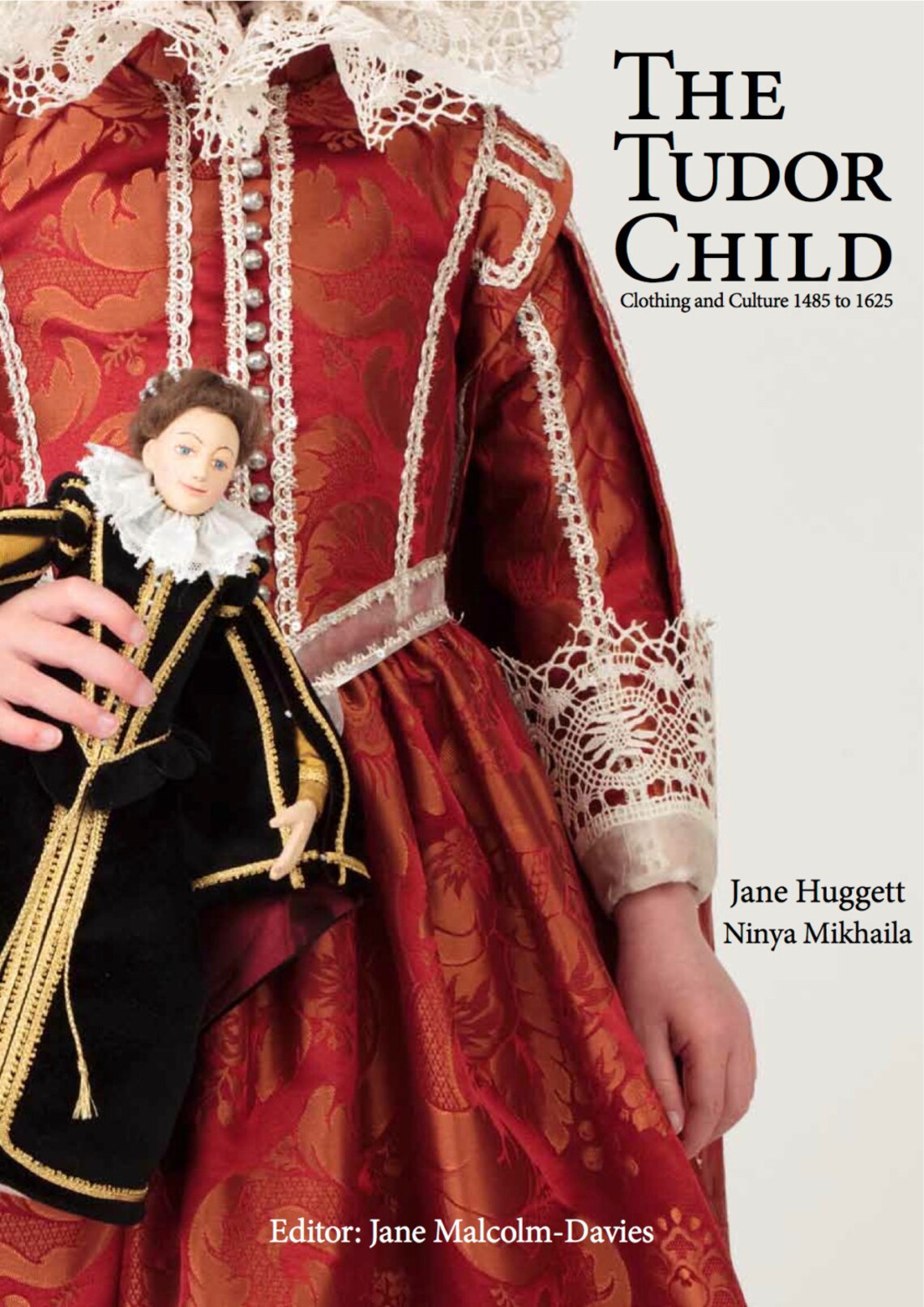

The Tudor Child: Clothing and Culture 1485-1625 by Jane Huggett and Ninya Mikhaila (ed. Jane Malcolm Davies).

I was expecting a slim research volume akin to

The Queen's Servants (which I love and will defend against all nay-sayers) and was pleasantly surprised at the depth and breadth of this book. It truly is

The Tudor Tailor for smaller persons. The main geographical focus is on England and northern Europe, with some Italian references also included. The book clocks in at 151 pages, excluding notes and index.

The first fifty pages are research: a brief peak into children's lives during the period, followed by explorations of garments for infants/toddlers, girls aged 4-12, and boys aged 4-12. While few garments survive for this period, they still manage to feature several garments or garment fragments, as well as period paintings, sculpture and even stained glass which depict children. All of the illustrations are color photographs. There's a further 12 pages discussing the materials used in children's clothing, including the different colors which can be documented. The construction section includes a couple of pages on general sewing techniques (pleats, gathering, buttonholes, making thread and cloth buttons, different seam finishes), as well as advice on selecting materials and on using the patterns. The patterns compromise nearly half the book (over 80 pages).

The patterns in this book are for children 0-12, both boys and girls. Except for the basic garments, which are given in two-year-age intervals, most of these are given in a single size: some re-scaling and fitting will be required to take full use of this book. Fortunately, basic instructions are provided. The projects included are:

- Childbed linen for 0-3 month old (elite and simple versions)

- Knit waistcoat for 3-6 mo, and infant petticoat

- Shirt and smock (for 8 year-olds, but with instructions to adjust for all-sized children)

- Bodies (c.1591) for a 6 year-old

- Spanish farthingale for a 10 year old

- French farthingale for a 2 year old

- Basic doublet, bodice and sleeve patterns* for 2, 4, 6, 8, 10 and 12 year-olds

- Skirt patterns* (sized for an 8-year-old, with instructions to scale up and down)

- Doublet, hose and coat for a 6 year-old boy (early 16th century)

- Coat and petticoat for a 6 year-old boy

- Doublet, breeches and coat for a 10 year-old boy (late 16th century)

- 1560s Kirtle and coat/gown for a 4-year-old

- 1560s Waistcoat and petticoat for a 12-year-old girl

- 1520-30s Kirtle and Gown for a 6-year-old girl

- 1546 Petticoat, kirtle, foresleeves, and gown for a 10-year-old girl (Elizabeth I portrait)

- 1547 Jacket, hose and gown for a 10-year-old boy (Edward VI portrait)

- 1565 Kirtle and gown for a 10-year-old girl

- 1588 Petticoat and coat for an infant (8 mo)

- 1600-1608 Doublet and petticoat for a 2-year-old

- Loose gown for a 12-year-old girl (1580s-1620s)

- Bodies, petticoat, and gown for a 6-year-old girl (1600-1640)

- Aprons, bibs, ruffs, collars, cuffs

- Biggins, caps, and coifs

- Frontlets, bonnets, and French hoods

- Caps, bonnets, and hats

- Stockings, mittens, and shoes

- A doll

*These are used together to make coats, gowns, petticoats, etc.--not "bodice and skirt" separates.

For all of the garments, a small chart is included to indicate whether the garment was used by lower, middle or upper class children, and whether it is appropriate to the beginning, middle or end of the Tudor period (approximately 1485-1540, 1540-1580, or 1580-1625). Some styles are used by all, others show up only in upper class clothing or linger in lower class use after elite fashion has moved on.

The best part is that each garment and ensemble is modeled by adorable children--it's like a series of Bruegel and Holbein paintings come to life. Additionally, there is a two-page photo tutorial showing how to properly swaddle a very young infant (0-3 months), and another showing how women's garments can be adjusted for pregnancy.

Overall, I think this is a fabulous book. It branches out a little from the adult volume--including a handful of knitting projects, as well as a basic infant turnshoe. With a little work to scale and fit, one could easily use this book to construct garments suitable for children of all ages and classes, from the late 15th to early 17th century. Some of this could also be done by scaling down

The Tudor Tailor's adult patterns to child-sized, but I wouldn't recommend that unless you're really strapped for time/money, have good drafting skills, and are clothing larger kids (infants and toddlers have some different styles than adults, even more so than older children).

Stars: 5

Accuracy: Pretty

High. A few original garments, but many original paintings; there is explicit explanation of what information is currently available about children's clothing in the period, and what is inference or speculation. Each garment pattern has margin notes about the sources it is based on.

Difficulty: Intermediate to advanced. Ambitious beginning sewists with good spacial reasoning and/or a mentor may also be able to make garments, particularly the basic ones. For less experienced sewists there is both basic sewing instruction and scaling/fitting advice included.

Overall Impression: I think this is an interesting and worthwhile book in its own right, and would recommend it to anyone clothing children from the late 15th to early 17th century, or interested in learning about children's clothes from that period.