Looking back on this year, it mostly didn't go to plan. I did a little mending and worked on some long term projects, but mostly only wrote up my culinary experiments. I also spent more time on knitting projects than I had anticipated.

Main Wardrobe Goals (c.1855-65)

Four chemises. I did a lot of emergency make-it-work-one-more-day repairs, but didn't get the nice ones done.

Four pairs of drawers. Ditto.

Four pairs of everyday stockings. Started sorting these, but didn't make any new ones.

Silk and wool stockings maintained. Also made new wool stockings.

Quilted and corded petticoats maintained. Took my corded apart and still need to get it on the new waistband.

Three nice white petticoats. Repaired the one where some of the stroked gathers came out.

Four usable collars (most 1855, one 1860s). Currently at 3 for 4.

Four useable sets of undersleeves or cuffs, suited to the dresses (most 1855, some later)

Make or re-make one work dress (1855)

One fashionable ensemble (1855). Arguably my blue plaid, which I did alter. However, the sleeves still tear out every time I wear it, so there's more alterations in its near future.

Two aprons. Repaired both the pink print and my white sewing apron.

One nice bonnet (1855) It has problems, but technically my white crepe meets this.

One sunbonnet Techincally true: the purple plaid's still holding on, and I have been working on its replacement.

Winter Mantle (c.1855) Posted just under the wire.

UFOs

Embroidered coif. Slowly progressing.

That red-print Empire gown. Paused with finished bodice, skirt, and sleeves needing to be joined, but I haven't touched it since Jan 2020 and it probably will need to be re-sized now.

Repair sewing kit. Needs to be a priority in 2023. I use it all the time, but the cardboard is truly given out.

Puffed Undersleeves. Paused from January 2020, though not for a particular reason.

Straw soft-crown bonnet. Nearly done!

Stretch Goals (I have materials but no pressing needs)

New 16th century kirtle and gown Did preliminary drafting and fitting, but not complete.

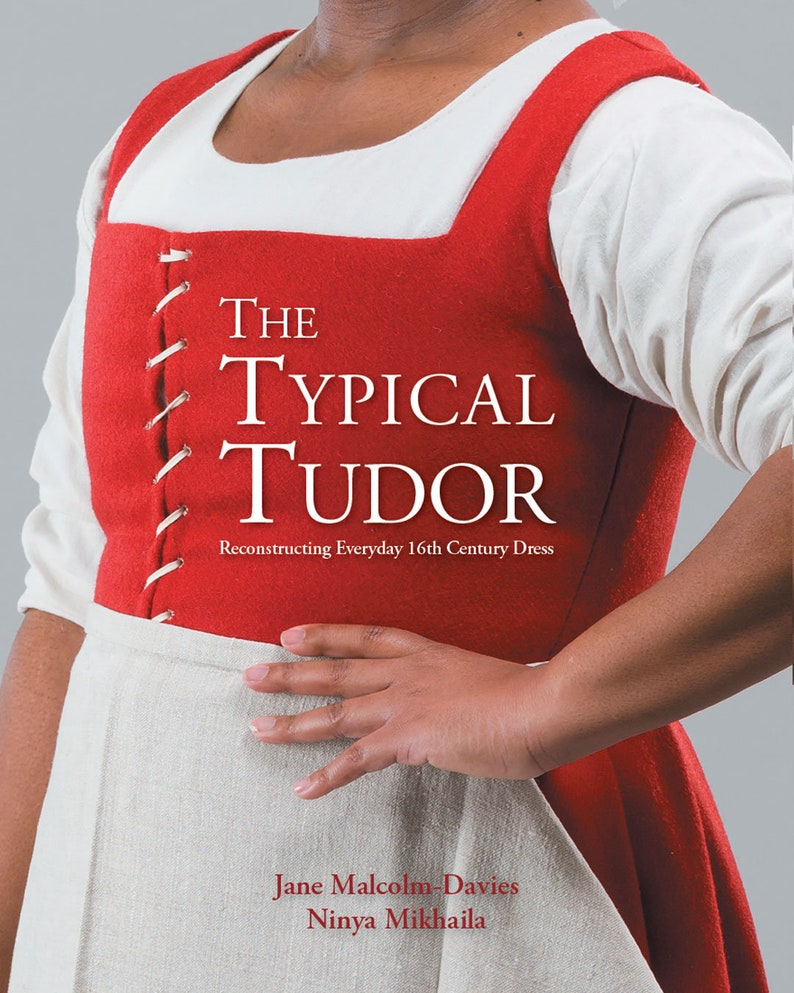

New 16th century smock Was waiting on Typical Tudor

Linen sheets

Tablet or pick-up woven bands Not exactly.

18th century peignor Still paused with a million yards of ruffles to hem.

18th century short gown and petticoat

18th century skirt supports for fancier gowns

18th century pocket

18th century hair pads

18th century cape Actually making good progress on this.

Empire pelisse

Coarse straw bonnet

Net lappet cap, 1850s

1870s spoon-busk corset

1900s corset

1912 Wrap Cloak Mock-up cut out, still fussing with the dart adjustments.

Undergarments for early 1900s traveling suit

1940s/1950s skirts and dresses One finished. And a second almost done.

Dancing slippers

Knit Stockings Modern. Period for the early 20th century technically...

Refresh 1860s bonnets

New 1800s/1810s bonnet

Bathrobe. Drafted and cut out. Sewing in progress.

Unplanned projects:

A Whole Bunch of Muffatees

Apron from The Workwoman's Guide

Mending posts? I did one or two (and three). There was more mending that never got written up, though not as much as I would have liked to get done.

Research posts? I didn't post any of these, but made substantial progress on four, which should go up early in the new year.

Drafts: 88

.jpg)