Wednesday, July 31, 2019

Wimple Wednesday: Early 1770s Ruffled Cap

Pattern from The American Duchess Guide to 18th Century Dress. There it's made up in organdy with lace; mine's of sheer linen (from Fabric-store.com, again), and is all hand sewn, as usual. Please excuse my uncooperative hair.

Tuesday, July 30, 2019

Miscellaneous Thoughts on Hair Dressing

| La Toilette (1858) Joseph Caraud |

Mostly with the mid-19th century in mind:

*Some sort of oil/pomatum really helps achieve the 'slick and neat' look so favored in the mid-century. I've also found that thoroughly soaking the hair can be effective. This is my preferred option on days when I need to go directly from a period event to a modern one, as sleek oiled hair can read as 'dirty' in modern styles.

*Bobby pins are meant for bobs--for guiding short hair into position. Hairpins are better suited to long hair and bulky updos.

*Staight-legged hair pins do not grip the same way wavy ones do--that's why wavy legged pins were invented and have remained popular. For best effect, insert the pin in the opposite direction from where you want to end up, then flip it around and weave it into place. Sliding it in makes it easy to slide out again. You will still lose pins, but less quickly.

*A lot of hair can be put up with surprisingly few pins. I can do a mid-19th century 'do with as few as four, and for 16th century I've managed with a single hairpin, or even none at all (wrapped braids and a linen rail help).

*Freshly-washed hair tends to slip and rebel a little more than hair washed a few days earlier. If you have to wash your hair that same day, try putting it up damp rather than fully drying it.

*Hair elastics didn't exist in the mid-19th century; I try to avoid using them, favoring thread or ribbon or nothing at all. If you need to use elastic to fasten off a braid, try using small bands that are transparent or else ones that close to the color of the hair, and then tuck them into the coil/chignon.

*Smooth your hair with a natural bristle brush to distribute applied oil/pomade and to get a neat look.

*Rats can be made in various shapes to fit the look you're going for. They do need to be replaced periodically, as they can get matted and flat.

*Whatever your hair's default color or texture, people in the period had it, and you can make accurate hairstyles. Dyed and cut hair is trickier. Consider your living history goals, the standards of the event you are attending, and your resources: clever arrangement may temporarily conceal a jaunty color, supplemental hairpieces can fill out short hair in an updo. Look, also, at historic photographs: though not prevalent, you can find occasional examples of women with short hair (generally parted and curled like a small child's short hair). For very dramatically modern hair, a covering sunbonnet or wig may be useful.

*Practice. Get the techniques into your muscle memory, and figure out which elements suit your particular style of beauty.

Monday, July 29, 2019

English Camp, 2019

|

| The Encampment on Garrison Bay |

Friday, July 26, 2019

Belts, 16th century

Getting into the spirit of Faire season by posting my outstanding Tudor resource posts.

|

| Belt buckle, German, 1520-1530. From VAM. |

|

| Belt buckle, German, 1520-1530. From VAM. |

| Belt hook, 15th century, French. From the MET. |

| Women's woven belt, Italian, 16th century. The MET. |

| Katharina Merian. German c.1536-1552. From the MET. |

| German woman. 1533. From the MET. |

|

| Unknown Lady. c.1575. UK National Trust. |

|

| Nazareth Newton, c.1578. UK National Trust. |

Thursday, July 25, 2019

What Should Be Worn and What Should Not

Frank Leslie's Lady's Magazine January 1864

WHAT SHOULD BE WORN, AND WHAT SHOULD NOT.

Novelty is ever one of the principal charms of the toilette; even those who care but little for personal adornment, and are apathetic on the subject of the latest arrival of fashions from Paris, seldom fail to make the inquiry from their dressmaker when issuing orders, “ Whether there is anything new ?" Such is the love of the toilette at the present day, and so great, indeed, almost fabulous, are the sums annually expended upon it, that those dressmakers who make a study of their business might always be prepared to answer in the affirmative; for whether their customers choose to adopt it or not, there is always something new. The demand is great, and, thanks to inventive brains, the supply keeps pace with it. The French Court, with the fair Empress at its head, leads the way, and finds a host of imitators and‘followers in almost every eccentricity it chooses to adopt; and these followers are not confined to France alone, but may be found in every capital of the civilised world.

Sometimes it happens that, for the sake of change, an old fashion is taken again into favor, not precisely in the same proportions it formerly assumed, but the same style, with some slight modification...

TL,DR: Basques are back, but now cut with a waist seam. Flounces are in...and not in; mind how they are arranged! Also, crinoline shape is round for day wear, trained for evening. Dresses should be trimmed with bands of color-coordinated velvet or plush or those nice chenille fringes... Ball dresses have lots and lots and lots of light, diaphanous ruching.

Wednesday, July 24, 2019

Wimple Wednesday: Late 16th Century Coif and Forehead Cloth

Time-warping out of order again. I managed to lose my one-piece coif while re-sizing it, and never got a picture of it worn with the forehead cloth.

The coif pattern is a custom-sized version of the Patterns of Fashion 4 16th/17th century coifs that I used before. The forehead cloth is based on two examples in the Met; both forehead cloths from the last quarter of the 16th century. They are triangular pieces of linen, each 14.5" x 16.5", one of which has short ties on the two corners adjacent to the hypotenuse. Zoomed in, the grain of the cloth indicates that these were cut as half-squares, the long edge falling on the bias.

The linen is, yet again, 3.5 oz lightweight from Fabric-store.com, the lace is from The Tudor Tailor Etsy store, and the ties are (bleached) 1/4" linen tapes from Burnley and Trowbridge.

|

| Third time's the charm. |

The coif pattern is a custom-sized version of the Patterns of Fashion 4 16th/17th century coifs that I used before. The forehead cloth is based on two examples in the Met; both forehead cloths from the last quarter of the 16th century. They are triangular pieces of linen, each 14.5" x 16.5", one of which has short ties on the two corners adjacent to the hypotenuse. Zoomed in, the grain of the cloth indicates that these were cut as half-squares, the long edge falling on the bias.

|

| Coif and forehead cloth. |

The linen is, yet again, 3.5 oz lightweight from Fabric-store.com, the lace is from The Tudor Tailor Etsy store, and the ties are (bleached) 1/4" linen tapes from Burnley and Trowbridge.

Tuesday, July 23, 2019

Three-Sided Reticule, 1831

|

| A nice, subtle design. |

From The American Girl's Book (1831). It's made of silk tafetta from Renaissance Fabrics (specifically, scraps from the plaid parasol), with tassels of dark blue silk floss, and red cord from my stash. All hand sewn, though not on purpose.

Here's an original bag of this style dated c.1800-1825 in the LACMA collection.

Monday, July 22, 2019

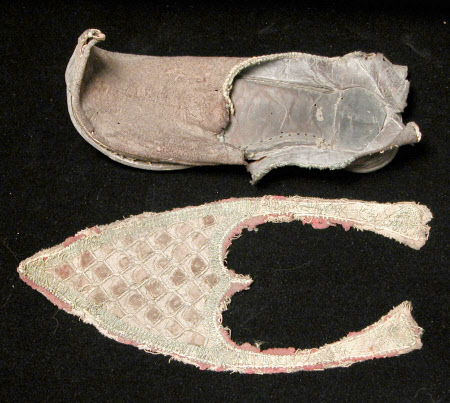

16th Century Shoes

A gallery of original shoes for inspiration:

|

| Shoe, English, 16th Century. UK National Trust. [I'm curious about the dating...these are pretty pointy.] |

|

| Slashed Shoe, early 16th Century. Museum of London. |

| Shoe, English, 16th Century. Met. And a similar "European shoe". |

|

| Slashed Shoe with Square Toe, c.1520-1540. VAM. |

| Shoe, British, 16th Century. Met. |

| Shoe, British, 16th Century. Met |

| Shoe, British, 16th Century. Met |

|

| Man's shoe, English, c.1530-1545. LACMA |

| Shoe, English, 16th Century. Met. |

|

| Velvet Shoes, French, c.1500-1550. MFA. |

| Leather Shoe, Italian, 16th Century. Met. |

|

| Shoe, English, c.1620. UK National Trust |

Sunday, July 21, 2019

HFF 3.15: Revolutionary

The Challenge: A revolutionary recipe, technique, ingredient, or a recipe from a revolutionary time.

The Recipe: Molasses Gingerbread from American Cookery (the first book of American recipes published in the US)

One table spoon of cinnamon, some coriander or allspice, put to four tea spoons pearl ash, dissolved in half pint water, four pound flour, one quart molasses, four ounces butter, (if in summer rub in the butter, if in winter, warm the butter and molasses and pour to the spiced flour,) knead well 'till stiff, the more the better, the lighter and whiter it will be; bake brisk fifteen minutes; don't scorch; before it is put in, wash it with whites and sugar beat together.

The Date/Year and Region: Hartford, Connecticut, 1798 (first ed 1796)

How Did You Make It: I mixed together 1.5 tsp cinnamon, 1 tsp coriander, and 2 lb flour, then rubbed into that 2 oz butter. To this, I added 1 pint molasses, and 2 Tbsp* baking soda dissolved in 1/2 cup of water. A thick, sticky dough resulted. I opted to bake it in a 9×13 pan; the gingerbread was fully baked after about 30 minutes at 350F.

* Should have been half this amount; the modern substitution seems to be baking soda = 1/2 amount of pearl ash. Next time, I may just have to order some real pearlash...

Time to Complete: About 15 minutes to mix up, and 30 to bake.

Total Cost: $5 for molasses

How Successful Was It?: Tasty, and just a tad dense. It was well received at the Regency Society picnic.

How Accurate Is It?: Pearl ash can apparently leave a bitter taste, which was not the case with the baking soda. Using the proper leavener or the proper (smaller) amount of the substitute may give a denser bread; made as it was, the dough doubled in thickness while baking. I probably should have mixed/kneaded the dough for longer, to make it truly stiff. I estimated the amount of coriander, as the receipt only said 'some'. I forgot the egg wash. The pan worked, but I need to do more research on when to use a flat pan versus a mold for gingerbread.

Friday, July 19, 2019

Walking Parasol, 1840s-early 1850s

A newly recovered 1840s/early 1850s walking parasol. It has a white-painted wood handle and baleen ribs.

|

| Before. |

The cover was badly tattered, though two of the panels were whole enough to trace as templates. The material (less faded on the inside) was originally a pink and purple plaid. It was pinked around the edge, unlined, and the panels seamed with a running stitch. A small circle of polished cotton, edges pinked in a V shape, was set between the rib hinges and the silk cover.

|

| New and old covers with frame and liners. |

|

| Fin. |

Wednesday, July 17, 2019

Wimple Wednesday: 1749 Cap

|

| Hair has to be dressed high on the back of the head to fit this one. Even though I scaled up the caul, as usual. |

This cute little ruffled cap is based on styles from the 1740s/1750s, and appears in The American Duchess Guide to 18th Century Dress. Mine is made of 5.3 oz mid-weight linen from Fabric-store.com, and about a million tiny hem stitches. Seriously. Each piece is hemmed along all sides, then gathered over fine linen cords and stitched down. The back drawstring is the linen cord from Burnley & Trowbridge

Tuesday, July 16, 2019

HFF 3.14: Ice

The Challenge: Ice

The Recipe: Strawberry Water Ices from The Art of Confectionery

The Date/Year and Region: Boston, 1865

How Did You Make It: Made a "32 degree" syrup by boiling 2 cups of water with 4 cups sugar (thanks to an 1914 source which actually defined the proportions); mashed 1.5 lbs of strawberries (then finished pulping them in the blender). Stirred both together with another 1/2 cup water, and the juice of 1 small lemon. Froze to solid consisency, put into 2 1-pint molds, and froze again.

Time to Complete: Aside from the freezing, about 20 minutes to mix up.

Total Cost: $3 for the fruit

How Successful Was It?: Very sweet, and with an intense strawberry flavor. Despite having fruit pulp instead of juice (or boiled peel), the texture felt very similar to other water ices I've made. Also, nothing caught fire this time, so I'd say it was "very successful".

The amount this made is a lot for just me, so in the future I'd scale it down by at least half--unless I was setting a full table for an event and needed two of the same molded ice)

How Accurate Is It?: Modern cheats include the blender and having an electric freezer for the molds. Materials are good; I omitted the cochineal, as the mixture's pink color was perfectly appealing to me, and I didn't want to mix up a whole batch for the few drops called for.

|

| The plating was my idea. Maybe there's too much mint... |

Saturday, July 13, 2019

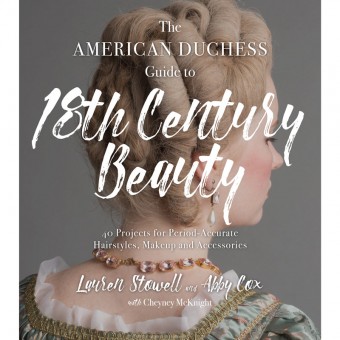

Book Review: The American Duchess Guide to 18th Century Beauty

For the first time, a timely review!

[Translation: my pre-ordered copy arrived today.]

The American Duchess Guide to 18th Century Beauty by Lauren Stowell and Abby Cox (with Cheney McKnight).

I've been excited for this book since I heard about it last January. First, because I like historic hair-dressing, and second because I have a lot of faith in the authors' work. Their previous book on 18th Century Dress-Making presented well-cited research in a straightforward conversational manner, lavishly illustrated with color photographs. The projects were all based on specific paintings, period publications and surviving artifacts; the techniques were from the period with some reconstruction (not make-dos for hiding modern methods).

Suffice to say, I had moderately high expectations coming in.

Those expectations were met. One of the first projects in this book is a hand-sewn sheer peignoir to wear while dressing one's hair. From that point, it's safe to say they owned my soul.*

This book matches its predecessor in size and heft; it's 215 pages from Introduction to Epilogue, exclusive of notes and bibliography. There are eight general hairstyles covering the years 1750 to 1795, each with its own cushion project (to support the hair in the desired shape) and a suitable cap. Five pieces of outerwear (2 hats, 2 bonnets and a hood), the peignoir, a few ornamental bows, and three hair pieces round out the sewn projects. There are also cosmetic recipes: 3 pomatums, 2 hair powders, 1 rouge, and 1 lip salve. All have step-by-step illustrated instructions. Some of the project instructions will refer to other ones (particularly to the pomading and powdering section), but I didn't find this distracting or hard to follow.

As with the dress book, the projects are clustered chronologically: each hairstyle is preceded by the relevant cushion project and any specific texturing techniques (curl, crape) and is followed by the appropriate cap as well as any bonnets/lappets/plumes. Four models appear in the eight tutorials, and there is discussion about adapting the techniques for different hair textures. Ms. McKnight contributed a two-page summary on how women of African descent living in Europe and North America in the 18th century dressed their hair.

Stars: 5

Accuracy: High. The models look like they stepped out of mid/late 18th century portraits, and sources are cited.

Difficulty: All levels. The hairstyles are labelled easy to difficult. Four pages of stitch tutorials are included for the less-experienced sewist (many projects, including all of the shaped hair-pads and accessories, require some sewing). I've not yet tried the hairstyles, as I need to make the pads and hairpieces.

Strongest Impression: This is a very useful resource for anyone trying to understand how late 18th century hairstyles actually work. I think it's invaluable for living historians interpreting c.1750-1795, but also for costume designers, artists, authors, and other people depicting women's life/behavior/material culture.

*The casual humor also won me over. I will happily pledge fealty to anyone who writes a serious book about historic hair-dressing methods while making their hard pomade in Darth Vader molds.

[Translation: my pre-ordered copy arrived today.]

The American Duchess Guide to 18th Century Beauty by Lauren Stowell and Abby Cox (with Cheney McKnight).

I've been excited for this book since I heard about it last January. First, because I like historic hair-dressing, and second because I have a lot of faith in the authors' work. Their previous book on 18th Century Dress-Making presented well-cited research in a straightforward conversational manner, lavishly illustrated with color photographs. The projects were all based on specific paintings, period publications and surviving artifacts; the techniques were from the period with some reconstruction (not make-dos for hiding modern methods).

Suffice to say, I had moderately high expectations coming in.

Those expectations were met. One of the first projects in this book is a hand-sewn sheer peignoir to wear while dressing one's hair. From that point, it's safe to say they owned my soul.*

This book matches its predecessor in size and heft; it's 215 pages from Introduction to Epilogue, exclusive of notes and bibliography. There are eight general hairstyles covering the years 1750 to 1795, each with its own cushion project (to support the hair in the desired shape) and a suitable cap. Five pieces of outerwear (2 hats, 2 bonnets and a hood), the peignoir, a few ornamental bows, and three hair pieces round out the sewn projects. There are also cosmetic recipes: 3 pomatums, 2 hair powders, 1 rouge, and 1 lip salve. All have step-by-step illustrated instructions. Some of the project instructions will refer to other ones (particularly to the pomading and powdering section), but I didn't find this distracting or hard to follow.

As with the dress book, the projects are clustered chronologically: each hairstyle is preceded by the relevant cushion project and any specific texturing techniques (curl, crape) and is followed by the appropriate cap as well as any bonnets/lappets/plumes. Four models appear in the eight tutorials, and there is discussion about adapting the techniques for different hair textures. Ms. McKnight contributed a two-page summary on how women of African descent living in Europe and North America in the 18th century dressed their hair.

Stars: 5

Accuracy: High. The models look like they stepped out of mid/late 18th century portraits, and sources are cited.

Difficulty: All levels. The hairstyles are labelled easy to difficult. Four pages of stitch tutorials are included for the less-experienced sewist (many projects, including all of the shaped hair-pads and accessories, require some sewing). I've not yet tried the hairstyles, as I need to make the pads and hairpieces.

Strongest Impression: This is a very useful resource for anyone trying to understand how late 18th century hairstyles actually work. I think it's invaluable for living historians interpreting c.1750-1795, but also for costume designers, artists, authors, and other people depicting women's life/behavior/material culture.

*The casual humor also won me over. I will happily pledge fealty to anyone who writes a serious book about historic hair-dressing methods while making their hard pomade in Darth Vader molds.

Friday, July 12, 2019

Godey's Lady's Book: Editor's Notes

Sometimes, the editor's messages in Godey's are the best part of the magazine. Yes, mostly it's just shipping confirmations to various initials, but the January 1865 issue is practically a novel:

Clara.— Rubber gloves are used for whitening the hands, price $2.50 per pair.

Mr. B. Clinton, New York.— We know nothing of the whereabouts of the lady.

Maud N. — Perhaps you are growing older. We cannot judge from your description.

I. L. E. — The authoress yon mention died some time since. She was an admirable writer, and her Incognita was well preserved.

Mary. — A frock-coat is an admissible garment for a gentleman to wear when he nuptializes.

L. E. R. — The photographers will "pose" you, as they call it, but they sometimes pose you out of all likeness. A plaid or striped dress is best.

Miss D. H. — We know of no method of making blue eyes look expressive. If they are "naturally melancholy in their expression," we presume it is natural.

E. H. — Tell him at once that you have lost the ring. He must have little faith In you if he cannot believe you.

Miss Q. A. O. — Under the circumstance that you were engaged, you should wear mourning.

Wednesday, July 10, 2019

Wimple Wednesday: 17th century backless cap and forehead cloth

The last cap (in this project) from Jane Arnold's Patterns of Fashion 4. It's dated to the mid-17th century, though I noticed a similar design in the VAM, listed as late 17th- early 18th century.

[Of course, this should have been last week's entry, but one of the strings disappeared at the last minute, and sewing another cap was faster than bleaching 12" of linen tape to match.]

The wearing method is somewhat tentative: the portrait featured in PoF4 shows only the front edge (the sitter's slightly angled and wearing a hat over the cap), so all we really have to go on is that it fits smoothly, and the lace goes along the face.

The cap has two loops at center back, which are intriguing: the cap needs to be joined or anchored around there to shape it to the head. There are also two sets of ties: long Y-shaped ones on the forehead cloth and very narrow tapes along the bottom edge of the cap. My best attempt has been to thread the cloth's ties through the cap's back loops, and then tie the tapes underneath my hair (back bun). The cap is then snugged slightly with the drawstrings and tied under the chin. The ties are a little short for comfort, but they are just long enough to fasten without trailing.

The fabric is light weight linen from Fabric-store.com; lace from The Tudor Tailor; ties are 1/4" and 1/2" linen tape from Burnley and Trowbridge (bleached white).

[Of course, this should have been last week's entry, but one of the strings disappeared at the last minute, and sewing another cap was faster than bleaching 12" of linen tape to match.]

|

| Looks weird, but it's quite comfy. |

The wearing method is somewhat tentative: the portrait featured in PoF4 shows only the front edge (the sitter's slightly angled and wearing a hat over the cap), so all we really have to go on is that it fits smoothly, and the lace goes along the face.

|

| The two cap pieces. Inside out, because I ironed them that way. The loops should be worked thread and the drawstring cord. |

The fabric is light weight linen from Fabric-store.com; lace from The Tudor Tailor; ties are 1/4" and 1/2" linen tape from Burnley and Trowbridge (bleached white).

Monday, July 8, 2019

Straw Bonnet c.1855

When you need a bonnet display stand quickly: use an iron.

The bonnet is made from 1/2" hemp braid bonnet, worked in the Timely Tresses Lydia Alma pattern (second shallowest brim length). Materials from the same: 4" sage-colored moire ribbon ties and bavolet, purple and yellow flowers with light green velvet leaves. Lace 'cap' inside the brim is a 1" cotton lace.

|

| This side has more flowers. |

|

| But I really like how the leaves look here. |

Sunday, July 7, 2019

Saturday, July 6, 2019

Partlet, 16th Century

|

| Black wool partlet, 16th century style. Photographing matte black fabric is not my favorite. |

This partlet is made of a single layer of black wool; it fastens with two pairs of ties under the arms and a single hook at center front. The ties are 1/4" linen from Burnley and Trowbridge, dyed with RIT as on my green apron (I'm always surprised when RIT gives me a good black, even though it's been consistently effective on linen; adding salt and heating it seems to work). It is entirely hand-sewn.

This partlet is inspired by one of the variations in The Tudor Tailor, but practically speaking, was traced off Elise's and then altered to fit me. I may have left the book at home that day...

Friday, July 5, 2019

Northwest History Conference

Our fair neighbors have a new conference for us Northwesterners: Manifest History.

It's in Hillsboro, OR, on October 18-19. Topics of daily life in the mid-19th century (not just dress) are on the agenda. And registration is open now.

Also, I'll be speaking at it. Do come!

It's in Hillsboro, OR, on October 18-19. Topics of daily life in the mid-19th century (not just dress) are on the agenda. And registration is open now.

Also, I'll be speaking at it. Do come!

Thursday, July 4, 2019

July 4

Not like the brazen giant of Greek fame,

With conquering limbs astride from land to land;

Here at our sea-washed, sunset gates shall stand

A mighty woman with a torch, whose flame

Is the imprisoned lightning, and her name

Mother of Exiles. From her beacon-hand

Glows world-wide welcome; her mild eyes command

The air-bridged harbor that twin cities frame.

“Keep, ancient lands, your storied pomp!” cries she

With silent lips. “Give me your tired, your poor,

Your huddled masses yearning to breathe free,

The wretched refuse of your teeming shore.

Send these, the homeless, tempest-tost to me,

I lift my lamp beside the golden door!”

--Emma Lazarus, "The New Colossus" (1883)

Wednesday, July 3, 2019

Wimple Wednesday: Early 18th Century Dutch Cap

Very similar to the (15th century, IIRC) open hood pattern in The Medieval Tailor's Manual, this early 18th century Dutch cap is cut in four pieces, joined with a center back seam and another running front-to-back along the top of the head.

The overall shape is of two squares with a short rounded bump at the center back; from the image, the peak is approximately 1/3 the total width of the cap, and 1/5 of its height. The original cap has an opaque fabric for the top of each side, with what appears to be a sheer embroidered material for the lower half of each piece (eye level to chin). There is a narrow lace edging around both hems; it's possible that the neck-edge hem contains a drawstring casing (as many of the Patterns of Fashion original caps and coifs do), but the available images do no show evidence of this.

I made my copy in light-weight linen (cut as only two pieces), without any hypothetical drawstrings. I measured it to account for my hair twisted into a coil at the back of the head, but after doing so think that I should have planned for coronet braids, and made the cap shallower.

| Dutch linen cap c.1700-1725 in The Met. |

The overall shape is of two squares with a short rounded bump at the center back; from the image, the peak is approximately 1/3 the total width of the cap, and 1/5 of its height. The original cap has an opaque fabric for the top of each side, with what appears to be a sheer embroidered material for the lower half of each piece (eye level to chin). There is a narrow lace edging around both hems; it's possible that the neck-edge hem contains a drawstring casing (as many of the Patterns of Fashion original caps and coifs do), but the available images do no show evidence of this.

I made my copy in light-weight linen (cut as only two pieces), without any hypothetical drawstrings. I measured it to account for my hair twisted into a coil at the back of the head, but after doing so think that I should have planned for coronet braids, and made the cap shallower.

|

| A simple linen cap, c.1700-1725. |

Tuesday, July 2, 2019

HFF 3.13: Solstice

The Challenge: Solstice. Try an astronomical- or astrological-themed recipe.

The Recipe: Meteors, from The Italian Confectioner; or, Complete Economy of Desserts [backup: meringues from Beeton's Book of Household Management, London, 1861]

The Date/Year and Region: 1827, London (also in The Art of Confectionery from 1865)

How Did You Make It: Boiled 1lb of granulated sugar in 3/4 cup water, while beating 3 egg whites to stiff peaks. I consulted with a modern guide to better understand the sugar-boiling stages, aiming for a 'blow', approximately 232F. The sugar boils though different stages, but I never got the diagnostic blow bubble. I ended up taking the sugar off when the thermometer got between 230F and 235F, then stirred in 1Tbsp of orange flower water (the 1865 receipt says to add coloring and flavoring at this point, though the 1827 receipt says nothing of flavors) and the beaten egg whites.

It didn't work.

Instead of a smooth, thick batter (liquid-ish confectionary substance?), the mixture stayed lumpy, with a transparent syrup layer below. Worse, it smelled strongly of egg.

As further mixing didn't improve matters, I went to plan B: make regular meringues. That is, do the same thing but with solid sugar rather than syrup.

I used Beeton's receipt (1/4 cup sugar per egg white, flavor as desired), and made small drops using folded parchment paper as a pastry bag. The meringues are definitely round, like various celestial bodies...

Time to Complete: About 50 minutes of boiling sugar; less than 10 minutes to prepare the meringues, before letting them dry in a cooling oven overnight.

Total Cost: All supplies were on hand.

How Successful Was It?: The meteors were not --like all my other attempts to boil sugar. The meringues were perfectly fine: the orange flower flavor is delicate and palatable and for the rest they are sweet and crisp. I do prefer these with vanilla as the flavor (and will eat the whole pan in one evening), but the orangeflower makes a nice change and is very Victorian .

How Accurate Is It?: Cheated with the modern electric mixer, as usual. I have, in fact, tried beating egg whites by hand before, and rarely succeed in producing stiff peaks (sore wrists, however...). I wish I had a wood-burning oven for making these, as it would be easier to get the right temperature.

|

| Meteors: not a success. |

|

| Meringues share a vaguely round shape with numerous celestial bodies like the sun, moon, and planets. |

Monday, July 1, 2019

Original: Striped Cotton Dress, c. 1804-1814

| Dress, American 1804-1814. From the Met. |

It's nice to see a cotton print dress from this period.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)