|

| Purse. |

|

| Interior, with frame for divider, and view of clasp apparatus. |

Compare with this illustration from Der Bazar:

|

| Der Bazar, 23 September 1861 |

|

| Peterson's, April 1861 |

| Silk and bead purse, American, 1860s. No dimensions given. |

|

| Purse. |

|

| Interior, with frame for divider, and view of clasp apparatus. |

|

| Der Bazar, 23 September 1861 |

|

| Peterson's, April 1861 |

| Silk and bead purse, American, 1860s. No dimensions given. |

|

| 1760. Thick Gingerbread from The Book of Household Management (1861) Also here, with better search functionality, but fewer illustrations. |

|

| Thick gingerbread. |

|

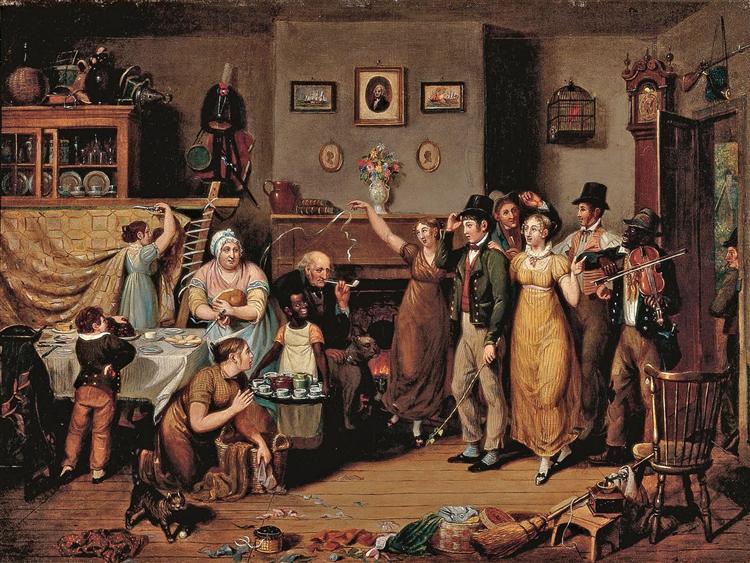

| A Quilting Party (1876) by Enoch Wood Perry |

BEE, a collection of people who unite their labor for the benefit of an individual or family, as a quilting bee.

--The English Language In Its Elements and Forms (1850)

The term 'Bee' although now almost obsolete, was but a few years since the fashionable title given, in the backwoods of America, to tea or scandal parties.

--Hogg's Instructor vol. VIII (1852)

BEE. An assemblage of people, generally neighbors, to unite their labors for the benefit of one individual or family. The quilting-bees in the interior of New England and New York are attended by young women who assemble around the frame of a bed-quilt, and in one afternoon accomplish more than one person could in weeks. Refreshments and beaux help to render the meeting agreeable. Husking-bees, for husking corn, are held in barns which are made the occasion of much frolicking. In new countries, when a settler arrives, the neighboring farmers unite with their teams, cut the timber and build him a log-house in a single day; these are termed raising-bees. Apple-bees are occasions when the neighbors assemble to gather apples, or to cut them up for drying.

--The Dictionary of Americanisms (1848)

Quilting-Bee or Quilting-Frolic. An assemblage of women who unite their labor to make a bed-quilt. They meet by invitation, seat themselves around the frame upon which the quilt is placed, and in a few hours complete it. Tea follows, and the evening is sometimes closed with dancing or other amusements.As many of these explanations indicate, the quilting bee is outdated by the 1850s. From a century and a half onward, it is an interesting experience to read so many authors lamenting the dissipated entertainments of their present day and reminiscing about the innocent amusements of their youth.

"We were as busy as bees to be sure, but then we were as blithe as a lark, and as merry as a cricket all the day long. We never even heard of the thousand ailments common now among young folks, and as to recreation, why we had more heart gaiety and frolic at a quilting bee, a sleigh-ride, or a paring match, than one of your fashionable belles enjoys in a whole year."

There are "quilting bees." where the thick quilts, so necessary in Canada, are fabricated... At the quilting, apple, and shelling bees there are numbers of the fair sex and games dancing and merrymaking are invariably kept up till the morning."

--The Englishwoman in American (1856)

The women have their bees as well as the men such as sewing been or quilting bees. A quilt is thus completed in a day that would otherwise be unfinished for months. The beverage of every meal, even of dinner, is tea; and how much better it is than whiskey or beer I need not say. I have heard in deed, that naughty things are said of the absent over the teacup; and I fear that sewing and quilting bees are not altogether innocent, but I am sure that a little female tea cup scandal is infinitely less than the evils of beer drinking and whiskey drinking. It may be necessary for me to hint that a ladies bee includes of course something nicer in the dietetic department than an out-door bee.

--Canada: Its Geography, Scenary, Produce, etc. (1860)

Among the home productions of Canada the counterpane or quilt holds a conspicuous place not so much in regard to its actual usefulness as to the species of frolic 'yclept a Quilting-bee in which young gentlemen take their places with the Queen-bees, whose labours they aid by threading the needles while cheering their spirits by talking nonsense. The quilts are generally made of patchwork and the quilting with down or wool is done in a frame. Some of the gentlemen are not mere drones on these occasions but make very good assistants under the superintendence of the Queen-bees. The quilting bee usually concludes with a regular evening party The young people have a dance. The old ones look on. After supper, the youthful visitors sing or guess charades.

--Twenty Seven Years in Canada (1853)

|

| The quiltings described by 1850s writers mostly look like this: industrious amusements of a simpler time, ie, the writer's youth. [The Quilting Frolic (1813) by John Ludwig Krimmel] |

"Coverlids [sic] generally consisted of quilts, made of pieces of waste calico, elaborately sewed together in octagons, and quilted in rectangles, giving the whole a gay and rich appearance. This process of quilting generally brought together the women of the neighborhood, married and single and a great time they had of it--what with tea talk and stitching. In the evening, the beaux were admitted so that a quilting was a real festival not unfrequently getting young people into entanglements which matrimony alone could unravel."

--Recollections of a Lifetime (1856)

The quilting generally began at an early hour in the afternoon, and ended at dark with a great supper and general jubilee, at which that ignorant and incapable sex which could not quilt was allowed to appear and put in claims for consideration of another nature. --"The Minister's Wooing", The Atlantic Monthly (1859)

Here we found a collection of women busily occupied in preparing the quilt, which you may be sure was a curiosity to me. They had stretched the lining on a frame and were now laying fleecy cotton on it with much care; and I understood from several aside remarks which were not intended for the ear of our hostess, that a due regard for etiquette required that this laying of the cotton should have been performed before the arrival of the company, in order to give them a better chance for finishing the quilt before tea, which is considered a point of honor.This and most other sources indicate that the quilting party was only for the actual quilting: any patchwork or applique was completed by the hostess well in advance. One story seems to allude to patchwork being done as a group activity: "The 'old married folks' have 'quilting parties' occasionally. They meet to sew together little bits of calico, and at the same time take the characters of their neighbors to pieces." (Burrillville: As it was, and As it is, 1856) However, this could just be a verbal counterpoint to 'taking their neighbors to pieces'.

--Forest Life (1842)

|

| Rolls, preserves, cheese, and loaf cake. A tasty day! |

|

| Mince Meat Pie |

|

| Portrait of Eliza Leslie, ie, My favorite advice-giving Victorian. Said to be 1844, but the bonnet looks more 1854. |

There's a lot of period literature available on-line (thanks, Google Books, Project Gutenberg, and Internet Archives). Here are a few of my favorite stories and books for period mores and material culture.

10. "Why Do the Servants of the Nineteenth Century Dress As They Do?" (1859) Yes, you're getting above your station. Stop it. An interesting look at changing class markers in England, as well as being impressively long-winded for such a short pamphlet. It also deliberately spells out that imitating high-fashion in cheap materials is vulgar.

9. "My Economy Quilt" (The Ladies' Repository, 1860): All the details that go into making a patchwork quilt, and throwing the party to assemble it (told in the form of "and then this went wrong").

8. "My Patchwork Quilt": The life-cycle of clothing through a patchwork. A good overview of not only changing dress styles, but also of a girl's sewing education and growing up.

6-7. (Tie) The Lady's Guide to Perfect Gentility (1856) and Hints on Etiquette and the Usages of Society With a Glance at Bad Habits (1844) Both of these etiquette manuals have their uses: the latter is more succinct, and somewhat addressed to gentlemen; while the former includes extensive notes on beauty rememedies, section II has a lot of good (and highly quotable) lady-specific information about comportment in various situations.

5. "My Velvet Shoes" (Harper's, 1860): A story chockful of prices and priorities at the lower end of the middle class. I was particularly impressed at how quickly fashionable hoop shapes apparently changed (every 2-3 months).

4. Half A Century: by Jane Grey Swisshelm follows her life from childhood, through various careers as a teacher, lecturer, newsaper publisher, and nurse in Pennsylvania, Minnesota, and Washington, D.C. It's very informative, especially on the Lyceum circuit and on women volunteers in wartime hospitals, but is also a retrospective written some years after the events took place. (Crusader and Feminist contains some of the author's contemporary writing).

3. "Dress Under Difficulties" (Godey's, 1866): While specific to the blockaded South, this article not only gives a number of ingenious home-made make-dos, but also offers some insight into how long clothing was normally expected to last, and the importance placed on keeping garments up to date.

2. Letters to Country Girls (1853) by Jane Grey Swisshelm. Cheeky, practical advice that's almost as informative for its suggestions as for its assertions of how you are managing your home and garden all wrong.

1. The Behavior Book (6th Edition 1855) by Eliza Leslie covers etiquette for all occassions, which ends up incorporating lots of information about everything from arranging a tea party to buying ribbons to tipping servants. I particularly like the the insight into how shops, omnibuses, and boarding houses operate. The conversational style (in my opinion) makes for a more engaging read than most other etiquette books.

|

| Finished jams and jellies: apple, currant, and yellow plum. |

|

| Sally Lunn Buns |