Regency Women's Dress: Techniques and Patterns 1800-1830 by Cassidy Percoco.

"Dress" is not limited to dresses: this book contains patterns for two chemises, two sets of stays, and three outer-garments (two spencers and a morning robe), as well as nineteen dresses. The earliest date on any garment is c.1795, the latest c.1827. The narrow scope and large number of examples allow for greater specification than in many books of this type. The "type" being books diagramming the construction of garment artifacts, such as Janet Arnold's

Patterns of Fashion series or Jill Salen's

Corsets: Historical Patterns and Techniques.

The book starts with a three-page overview of fashion changes through the ~30 years in question; I liked that the table of contents employed sketches of each garment, making a nice fashion timeline for comparison, as well as a visual reference. Each garment featured in this book in an original from the late 18th/early 19th century, with full citation. All the garments are held in American collections (mostly in New York, or else Old Sturbridge Village in Massachusetts). Knowing the whereabouts of each garment is useful, in that looking up additional images of the garments online is almost required in order to make any of them.

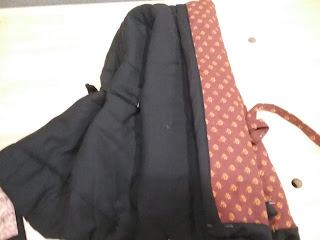

I really love the scaled pattern diagrams of each garment (two pages), the inclusion of contemporary images and fashion plates (most of one page per garment), and the description of how the garment is assembled (also most of a page). Each garment also gets a colored photograph, and a pencil sketch. The problem I'm having with making any of these garments is the lack of comprehensive images: the line drawings are front-view-only, as worn, and the photograph is always a detail shot. While this is great for seeing the fabric (and occasionally the interior), not seeing the whole thing is really hard when you're trying to actually construct something. There's a ~3" tall line-drawing of each finished garment, shown from the front only as it is worn, but that's like trying to sew from the image on the back of pattern envelop (with no back view included). The assembly information is descriptive rather than instructive--which makes perfect sense, but also makes internal and back views

more necessary, for figuring out which seams should cross over which others, etc. Particularly for things like figuring out how to fasten the bib-front dresses (pins? buttons? additional ties?), there is simply not enough information included in the written instructions, and not enough back or internal views of the finished garment (photograph or sketch) to answer the question.*

The format begs for comparison to the

Patterns of Fashion books: I think that

Regency Women's Dress makes a nice addition to this genre for its narrow temporal focus, and inclusion of multiple garment types. I also like the color photographs of garment detail and the use of contemporary illustrations for context; but I think that the lack of detailed whole-garment sketches makes this book harder to use than

Patterns of Fashion.

Stars: 3**

Accuracy: Very high. All original garments, with some useful context.

Difficulty: Advanced. Additional sources or a lot of assembly know-how will be required to make the garments (above the usual 'scale and fit' skills).

Strongest Impression: Potentially a nice all-in-one reference for Regency/Empire styles, including undergarments, dresses, and some outerwear. However, there isn't quite enough construction information (and/or detailed images) to make the garments without consulting additional sources. A good reference for costume designers, and almost an amazing one for reconstruction sewing.

*For the other garment I've tried so far, a

chemise, an internal photograph of the sleeve seams would have make construction infinitely easier. The written description of joining the sleeve to the main garment was almost impossible to follow: the sleeve is encased in the two-layer strap, and that is then sewn to the front/back pieces. How, then, is the sleeve attached to the front/back without leaving a weak raw edge or a lumpy transition to the felling? A photograph would have solved this instantly: instead, I spent a lot of time trying to find photographs of similar pieces, and finally ended up sewing several half seams, tacking down other pieces, and going back to finish seams out of order. Even so, there's a slight lump where the sleeve seam allowance transitions from being faced to being felled.

**I revised this down to three stars after attempting a further three garments from this book. Between scaling issues on the stays, a lack of fastener information on the bib-front dress, and sorely needed construction explanations on both gowns, this is simply not an easy book to use. You really need additional sources (or, ideally, a picture or sketch of the interior and back view of the garment) to actually make most of the garments I've attempted.