To refresh, here are the frill instructions:

Cast on 90 stitches with white wool, and knit 3 rows before commencing the pattern.

1st row Slip1, knit 1, a pearl 1; knit 2 together three times; repeat from a, finishing with knit 2.

2d. Slip1, knit 1, a pearl 1, knit 12; repeat from a.

3d. Like 2d row.

4th. Slip 1, pearl 1, a knit 1, pearl 12; repeat from a.

Repeat rows 1-4 5 times (total of 3 rows plain and twenty rows pattern) in white, and then once (4 rows) in colored wool.

These four rows form the pattern, which must be repeated five times with white, then once with blue, and cast off loosely. Two frills are required for each sleeve: the upper is placed about an inch and a half above the under, which is sewed by the edge of the sleeve.

These frills are a bit problematic, as there's an error in the instructions. The many "knit two together" instructions in line 1 are not balanced by making new stitches anywhere; therefore, the total number of stitches drops by almost half every fourth line. Like this:

|

| The frill as written: after four repetitions, there's only a dozen stitches left. |

I'm not the only one to notice this problem. My solution to it, in attempting to keep as close to the written instructions as possible, was to simply add a yarn over before each 'knit 2 together'. This creates a series of small eyelets in each fourth row of the motifs. It's not nearly as open as the illustration suggests, but it's a pretty effect, and should be plenty warm (and I'm not a sufficiently experienced knitter to get too creative here). In the interest of making the motifs match-up, I decided to make the first and last 2 stitches into a stockinette stitch, and use sequences of 6 knits (or purls) between "ridges" on rows 2-4 instead of 12 (otherwise you get a 14-stitch repeat in the first row with a 13-stitch repeat subsequently). The purl-heavy fourth row made me suspect that a stockinette effect was intended. I initially tried carrying this through all four rows (first row largely as written, 4th row, 2nd/3rd row, 4th row), but thought that the eyelets tended to disappear; instead, I decided to go with "1st, 2nd, 4th, 2nd", so the three non-eyelet rows give a stockinette stitch with occasional ridges, while the eyelet row is opposite.

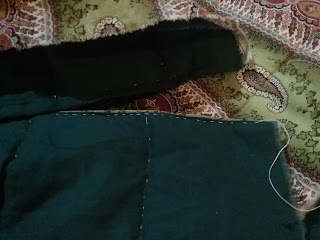

So, my revised frills:

Cast on 96 stitches, and knit plain for three rows in white yarn.

Motif:As per the originals, this four row motif is repeated four times in white, and once in color (I used purple instead of blue):

1st row: Slip 1, knit 1, [purl 1, yarn over, knit 2 together] 13 times, purl, knit 2.

2nd row: Slip 1, knit 1 [purl 1, knit 6] 13 times, purl, knit 2

3rd row: Slip 1, purl 1 [knit 1, purl 6] 13 times, knit, purl 2

4th row: Slip 1, knit 1 [purl 1, knit 6] 13 times, purl, knit 2

The frills are considerably more substantial than the open petals depicted in the magazine, but I think they also look a bit warmer. We'll see how they end up working. If I do this pattern again, I'd like to find a way to make the ruffles look more like the illustration (which will probably involve cookies and bribing a more experienced knitter to help).