The short version:

The second edition (1859) adds an additional entry to the above:

"The Spinning Wheel", an opinion piece that appeared in The Ladies' Wreath in 1852 asserts that:

- A "quilting bee", "quilting party", or just "a quilting" is a favorite topic for reminiscences and historical fiction in the 1840s-1850s. They are considered to be old-fashioned and nearly extinct; after 1860, these mentions dwindle.

- The quilt should be pieced and placed on the frame before guests arrive. With enough workers, it will be done in a single afternoon.

- The order of events is: quilting, a meal (tea/supper), dancing or parlor games, optional snack. The first part is for women; men are added at either step 2, 3, or 4.

- Common times to have a quilting are on winter evenings in New England, or when a young lady is about to be married. Quiltings are not limited to these circumstances, however.

|

| A Quilting Party (1876) by Enoch Wood Perry |

BEE, a collection of people who unite their labor for the benefit of an individual or family, as a quilting bee.

--The English Language In Its Elements and Forms (1850)

The term 'Bee' although now almost obsolete, was but a few years since the fashionable title given, in the backwoods of America, to tea or scandal parties.

--Hogg's Instructor vol. VIII (1852)

BEE. An assemblage of people, generally neighbors, to unite their labors for the benefit of one individual or family. The quilting-bees in the interior of New England and New York are attended by young women who assemble around the frame of a bed-quilt, and in one afternoon accomplish more than one person could in weeks. Refreshments and beaux help to render the meeting agreeable. Husking-bees, for husking corn, are held in barns which are made the occasion of much frolicking. In new countries, when a settler arrives, the neighboring farmers unite with their teams, cut the timber and build him a log-house in a single day; these are termed raising-bees. Apple-bees are occasions when the neighbors assemble to gather apples, or to cut them up for drying.

--The Dictionary of Americanisms (1848)

The second edition (1859) adds an additional entry to the above:

Quilting-Bee or Quilting-Frolic. An assemblage of women who unite their labor to make a bed-quilt. They meet by invitation, seat themselves around the frame upon which the quilt is placed, and in a few hours complete it. Tea follows, and the evening is sometimes closed with dancing or other amusements.As many of these explanations indicate, the quilting bee is outdated by the 1850s. From a century and a half onward, it is an interesting experience to read so many authors lamenting the dissipated entertainments of their present day and reminiscing about the innocent amusements of their youth.

"The Spinning Wheel", an opinion piece that appeared in The Ladies' Wreath in 1852 asserts that:

"We were as busy as bees to be sure, but then we were as blithe as a lark, and as merry as a cricket all the day long. We never even heard of the thousand ailments common now among young folks, and as to recreation, why we had more heart gaiety and frolic at a quilting bee, a sleigh-ride, or a paring match, than one of your fashionable belles enjoys in a whole year."

These writers are quite explicit that the quilting bee is rare by the mid-century. A story in The Lady's Album (1846) exclaims: "Reader--were you ever at a Quilting Party--an old fashioned quilting party? If not--you will do well to read our description, which, of course, must fall far short of the reality--and this reality, as the thing is now nearly obsolete, you may never have the satisfaction of witnessing."

Eleven years later, another short story refers to quilting parties as "quite old-fashioned", and goes on to relate a story from fifty years past, in which a quilting figures prominently.

Another interesting note is how often the non-fiction references to quilting bees are explanations aimed at urban readers, especially Europeans. The overall impression is that quilting bees/parties are largely a phenomenon of rural communities in early-19th-century America/Canada. Consider:

Another interesting note is how often the non-fiction references to quilting bees are explanations aimed at urban readers, especially Europeans. The overall impression is that quilting bees/parties are largely a phenomenon of rural communities in early-19th-century America/Canada. Consider:

There are "quilting bees." where the thick quilts, so necessary in Canada, are fabricated... At the quilting, apple, and shelling bees there are numbers of the fair sex and games dancing and merrymaking are invariably kept up till the morning."

--The Englishwoman in American (1856)

The women have their bees as well as the men such as sewing been or quilting bees. A quilt is thus completed in a day that would otherwise be unfinished for months. The beverage of every meal, even of dinner, is tea; and how much better it is than whiskey or beer I need not say. I have heard in deed, that naughty things are said of the absent over the teacup; and I fear that sewing and quilting bees are not altogether innocent, but I am sure that a little female tea cup scandal is infinitely less than the evils of beer drinking and whiskey drinking. It may be necessary for me to hint that a ladies bee includes of course something nicer in the dietetic department than an out-door bee.

--Canada: Its Geography, Scenary, Produce, etc. (1860)

Among the home productions of Canada the counterpane or quilt holds a conspicuous place not so much in regard to its actual usefulness as to the species of frolic 'yclept a Quilting-bee in which young gentlemen take their places with the Queen-bees, whose labours they aid by threading the needles while cheering their spirits by talking nonsense. The quilts are generally made of patchwork and the quilting with down or wool is done in a frame. Some of the gentlemen are not mere drones on these occasions but make very good assistants under the superintendence of the Queen-bees. The quilting bee usually concludes with a regular evening party The young people have a dance. The old ones look on. After supper, the youthful visitors sing or guess charades.

--Twenty Seven Years in Canada (1853)

|

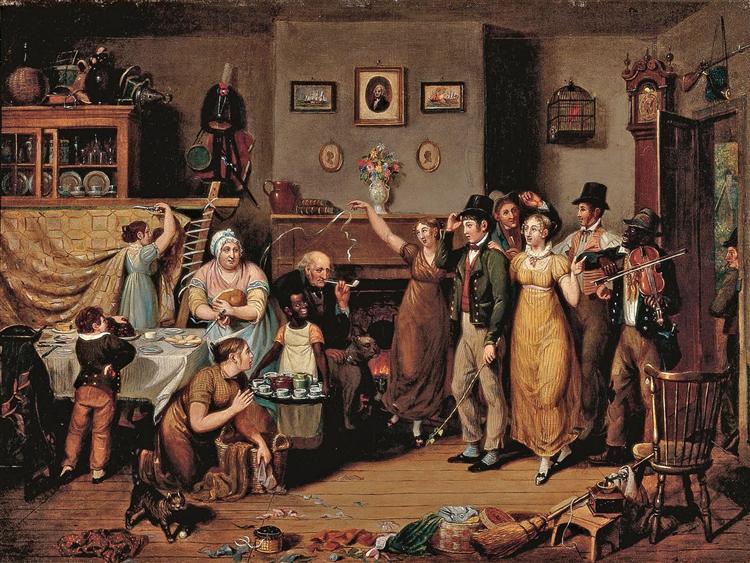

| The quiltings described by 1850s writers mostly look like this: industrious amusements of a simpler time, ie, the writer's youth. [The Quilting Frolic (1813) by John Ludwig Krimmel] |

A few stories allude to specific quilting parties in preparation for a wedding, but the majority do not. Excepting one story in which fifteen "misses" aged 14-20 gather to quilt for a friend's wedding, most of the descriptions explicitly describe both single and married women holding and attending quilting parties. That being said, the after-dinner amusements and flirtations are especially directed for the former. The need for gentlemen to escort ladies to and from the quilting also lends itself to flirtation and gossip.

"Coverlids [sic] generally consisted of quilts, made of pieces of waste calico, elaborately sewed together in octagons, and quilted in rectangles, giving the whole a gay and rich appearance. This process of quilting generally brought together the women of the neighborhood, married and single and a great time they had of it--what with tea talk and stitching. In the evening, the beaux were admitted so that a quilting was a real festival not unfrequently getting young people into entanglements which matrimony alone could unravel."

--Recollections of a Lifetime (1856)

The quilting generally began at an early hour in the afternoon, and ended at dark with a great supper and general jubilee, at which that ignorant and incapable sex which could not quilt was allowed to appear and put in claims for consideration of another nature. --"The Minister's Wooing", The Atlantic Monthly (1859)

Some of the quilting parties corresponded with a wood-chopping party for the men. Their separate work concluded with the daylight, both groups then meet up for dinner, which is followed by parlor games or dancing, with copious flirtation in either case. While the quilting portion was largely the domain of women (and the odd helpful brother), men are often invited for the concluding festivities, even when not preceded by a working party of their own.

Not all quilting bees produced a completed quilt. "My Economy Quilt" in The Lady's Repository (1860) deliberately emphasizes things not going as intended, and has the namesake quilt only half-done after an afternoon's work, thereby requiring another week of the maker's time to complete. Putting the quilt on the frame before the party started was one way to help ensure that a quilt was finished by the end of the day:

In "My Economy Quilt", the quilters' evening meal ("tea") includes 'nice biscuits, boiled custard, cold tongue and cheese and pickled peaches and preserved citrons and mince pie and loaf cake and sponge cake and tea and coffee', with a final serving of 'apples, and nuts, and raisins' before the guests disperse.' In another story, an afternoon's quilting ends with a "sumptous supper" served at dusk, which is then followed by dancing, and ends at 9 o'clock with cider and dough-nuts. The 1853 book Clovernook describes the preparations for a quilting party, including the purchase of "calico for the border of the quilt, with cotton batting and spool thread, but we also procured sundry niceties for the supper, among which I remember a jug of Orleans molasses, half a pound of ground ginger, five pounds of cheese and as many pounds of raisins". It goes on to note that "...before the appointed day every thing was in readiness--coffee ground, tea ready for steeping, chickens prepared for broiling, cakes and puddings baked, and all the extra saucers filled with custards or preserves." In a description in the American Agriculturalist (1847), it is stated the "bread and cakes are baked and every nice thing made ready for the feast the day before" the quilting party; in this case, men are not included in the supper, but they are "allowed to partake of the cakes, apples, and cider before the party breaks up"

While I could find little information about the proceedings, it appears that even enslaved women gathered for quilting parties.

P.S. For those looking for quilting pictures, Barbara Brackman has compiled some lovely images of women quilting, with commentary; she also discusses quilt frames of the 1860s (twice).

Not all quilting bees produced a completed quilt. "My Economy Quilt" in The Lady's Repository (1860) deliberately emphasizes things not going as intended, and has the namesake quilt only half-done after an afternoon's work, thereby requiring another week of the maker's time to complete. Putting the quilt on the frame before the party started was one way to help ensure that a quilt was finished by the end of the day:

Here we found a collection of women busily occupied in preparing the quilt, which you may be sure was a curiosity to me. They had stretched the lining on a frame and were now laying fleecy cotton on it with much care; and I understood from several aside remarks which were not intended for the ear of our hostess, that a due regard for etiquette required that this laying of the cotton should have been performed before the arrival of the company, in order to give them a better chance for finishing the quilt before tea, which is considered a point of honor.This and most other sources indicate that the quilting party was only for the actual quilting: any patchwork or applique was completed by the hostess well in advance. One story seems to allude to patchwork being done as a group activity: "The 'old married folks' have 'quilting parties' occasionally. They meet to sew together little bits of calico, and at the same time take the characters of their neighbors to pieces." (Burrillville: As it was, and As it is, 1856) However, this could just be a verbal counterpoint to 'taking their neighbors to pieces'.

--Forest Life (1842)

In "My Economy Quilt", the quilters' evening meal ("tea") includes 'nice biscuits, boiled custard, cold tongue and cheese and pickled peaches and preserved citrons and mince pie and loaf cake and sponge cake and tea and coffee', with a final serving of 'apples, and nuts, and raisins' before the guests disperse.' In another story, an afternoon's quilting ends with a "sumptous supper" served at dusk, which is then followed by dancing, and ends at 9 o'clock with cider and dough-nuts. The 1853 book Clovernook describes the preparations for a quilting party, including the purchase of "calico for the border of the quilt, with cotton batting and spool thread, but we also procured sundry niceties for the supper, among which I remember a jug of Orleans molasses, half a pound of ground ginger, five pounds of cheese and as many pounds of raisins". It goes on to note that "...before the appointed day every thing was in readiness--coffee ground, tea ready for steeping, chickens prepared for broiling, cakes and puddings baked, and all the extra saucers filled with custards or preserves." In a description in the American Agriculturalist (1847), it is stated the "bread and cakes are baked and every nice thing made ready for the feast the day before" the quilting party; in this case, men are not included in the supper, but they are "allowed to partake of the cakes, apples, and cider before the party breaks up"

While I could find little information about the proceedings, it appears that even enslaved women gathered for quilting parties.

P.S. For those looking for quilting pictures, Barbara Brackman has compiled some lovely images of women quilting, with commentary; she also discusses quilt frames of the 1860s (twice).

This was very interesting! Thank you. I appreciate all the and research you put into it. (:

ReplyDelete*time and research.* Sorry!

DeleteYou are very welcome.

Delete